See more about this Episode

Androgynous Black women with a nerdy love of sci fi and a sexuality shrouded in mystery don’t typically operate in the world of Hip Hop and R&B, but Janelle Monáe is the exception. Since she emerged on the scene ten years ago with her first EP Metropolis: The Chase Suite — introducing a seven-part concept series about a robot named Cindi Mayweather who’s navigating the strict social stratification in the year 2719 — Monáe has been building on those weirdo themes to tell stories of inequality and resilience. If Hip Hop and R&B deal with the raw, the real, the human, Monáe’s proclivities to the future are acts of dissent themselves.

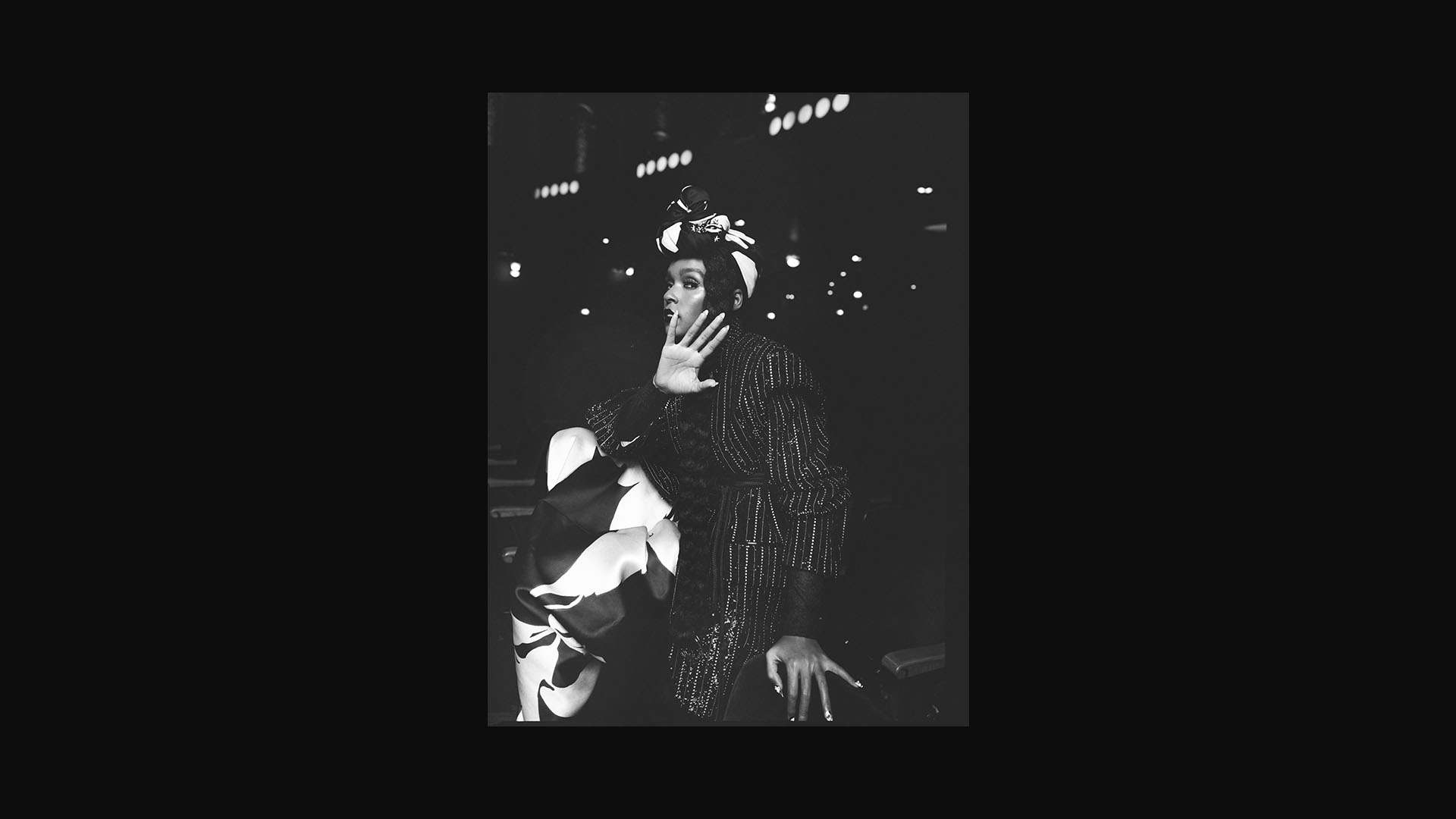

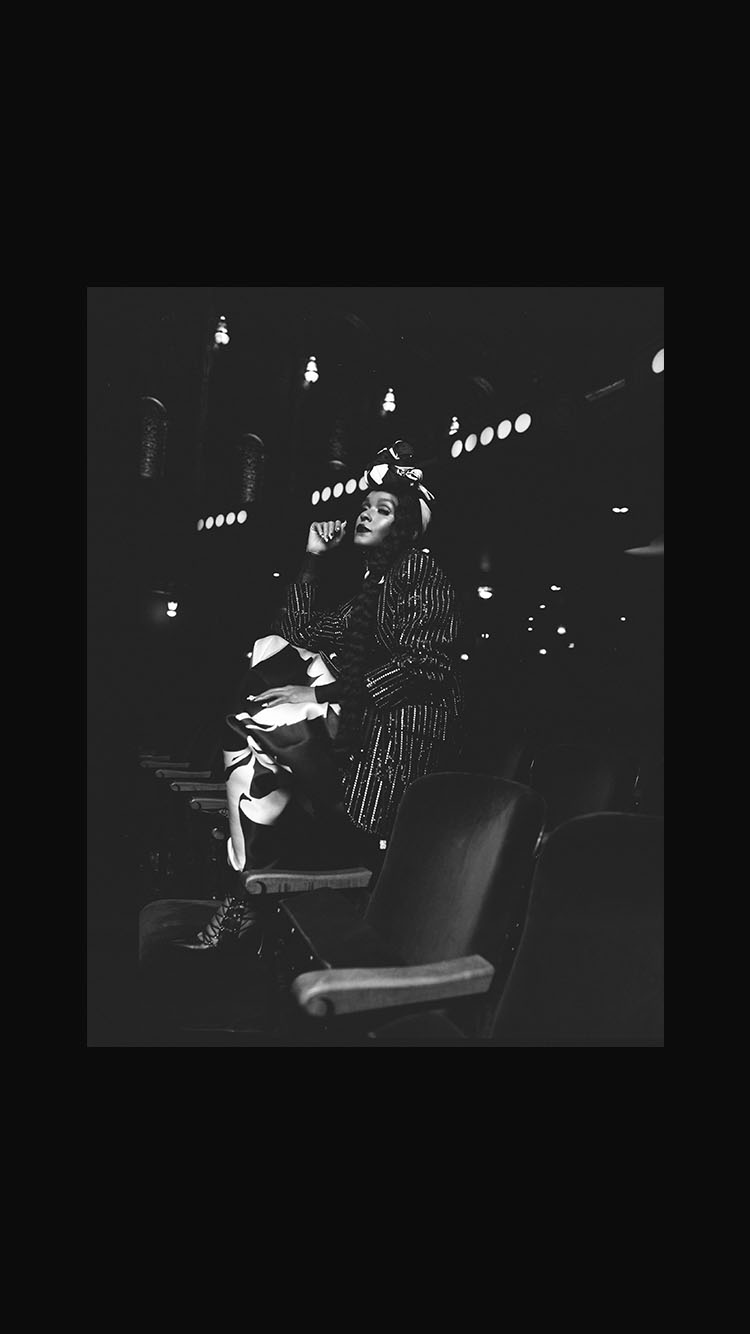

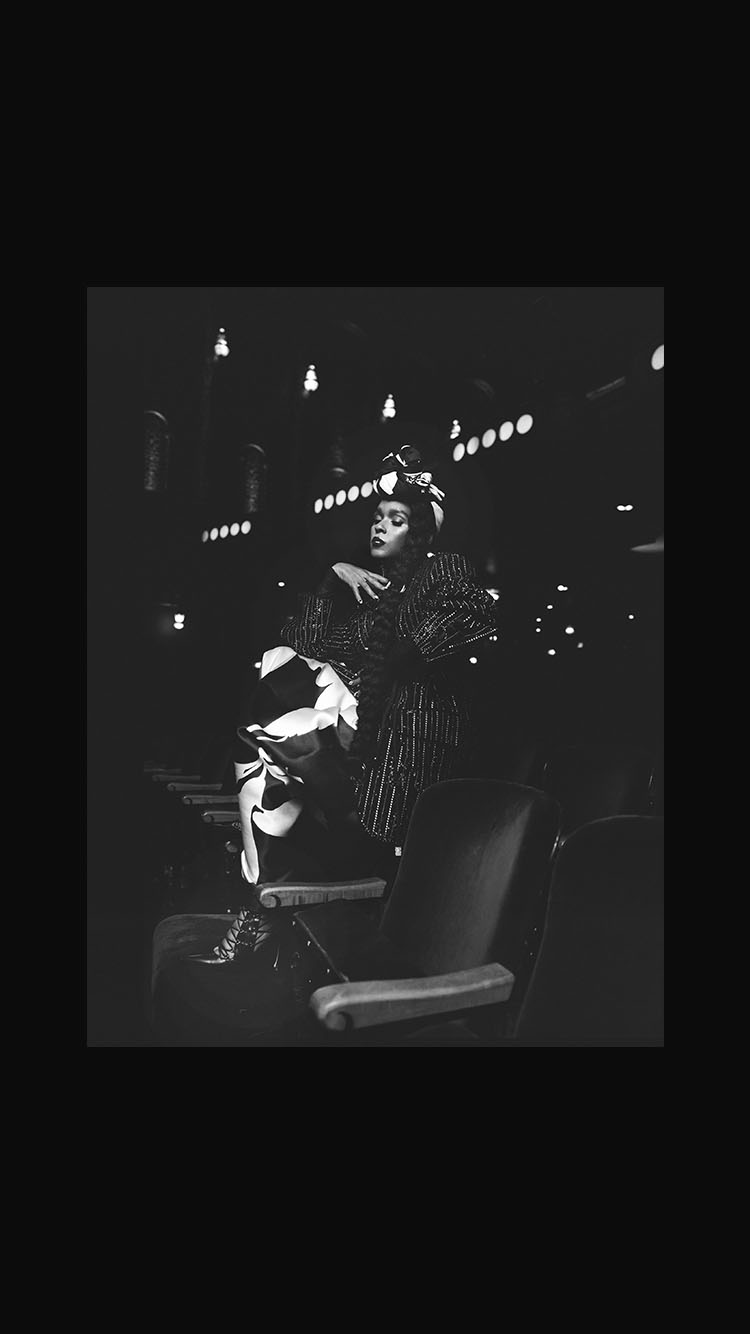

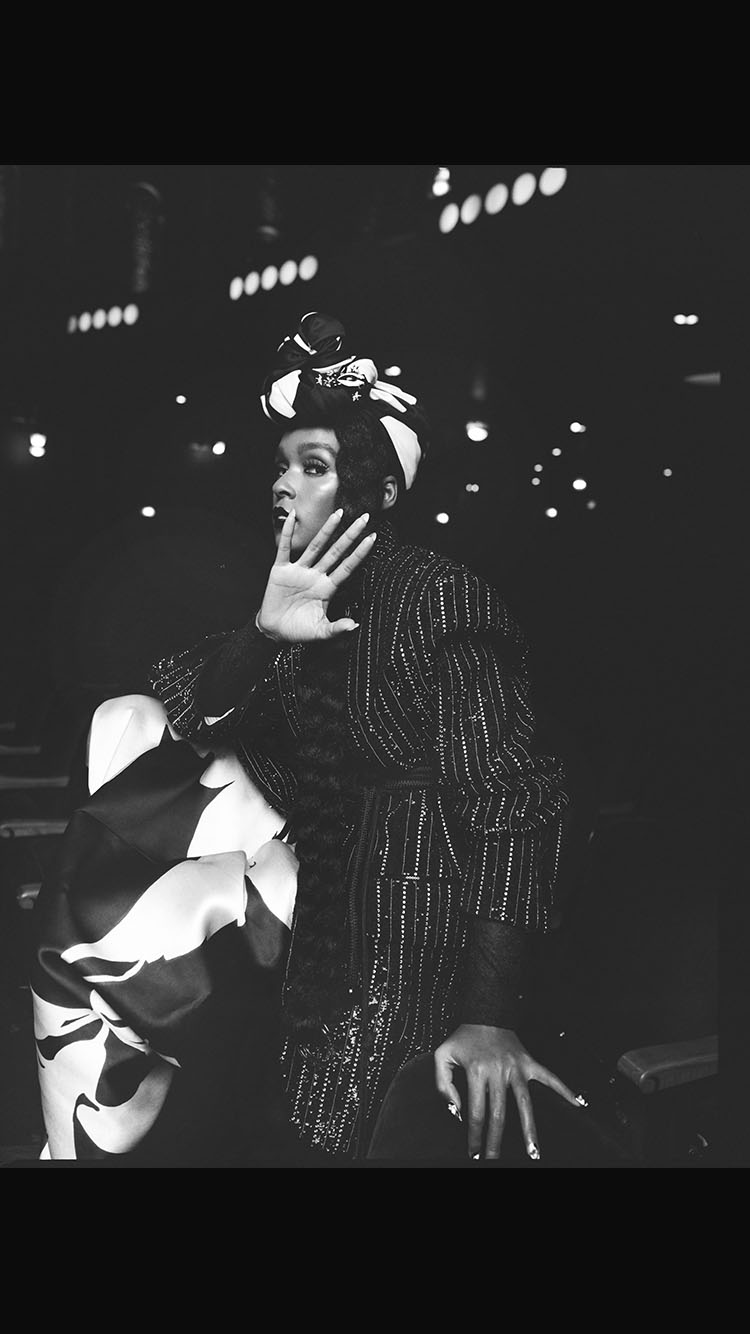

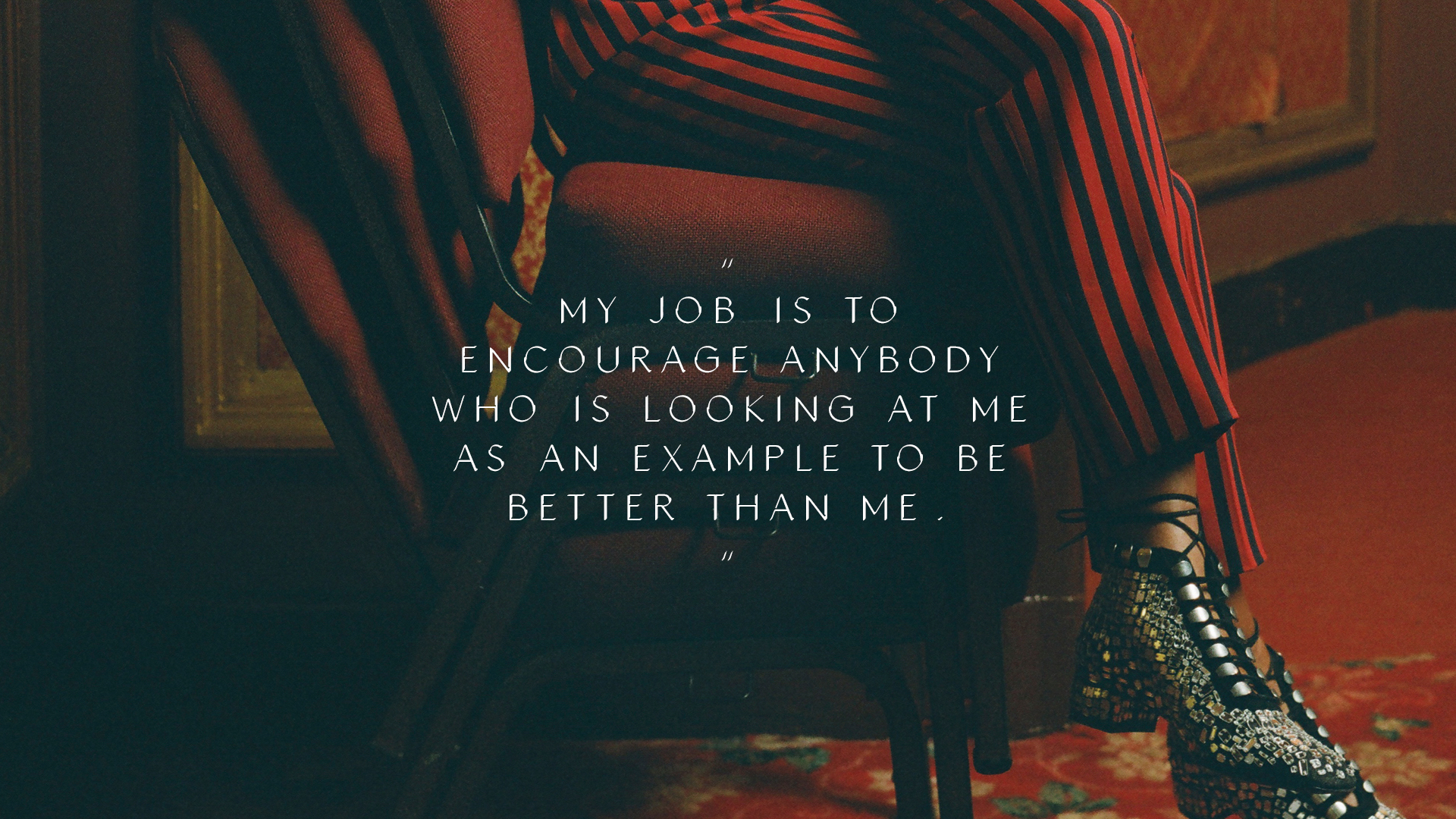

Marc Jacobs blazer, top, trousers, belt, and turban; Liudmila Footwear Drury Lane 100 Boots, €950, available at Liudmila Footwear; 3.1 Phillip Lim earring.

But that’s all different now. It’s her latest LP Dirty Computer, that feels the most prescient. Right as the world is questioning our dependence on hiding behind social media feeds and algorithms, Monáe is pulling back the curtain on her own cyborg persona. While everyone else is trying to protect their privacy — from Facebook, from Russia, from the government, from pop-up ads, from their exes — Monáe herself is standing where Cindi once did.

“Cindi Mayweather is still a part of me, part of who I am,” the 32-year-old Monáe tells me. “Dirty Computer is just where I am now. I'm being more vulnerable and even more honest. It deals with what it means to be erased.”

This is a quite literal description. In the Dirty Computer film, a 47-minute long musical that Monáe is calling an “emotion picture,” Monáe has fashioned a dystopia where a totalitarian regime has deemed some droids — like queer, polyamorous Jane 57821 — “dirty computers.” These faulty machines are cleansed by wiping away their memories. Interspersed between Jane’s attempts at resisting the ominous plot to strip her of her identity are her memories, each one represented by a music video of the songs on Dirty Computer. It is a visual and sonic fantasy that is exceptionally captivating. The cinematography is colorful and striking; the storyline is relevant, but not pandering. She is speaking directly to the experiences of people like me, who often find themselves at odds with conventional modes of living in today’s America. In the same way that Black Panther reignited the imaginations of Black children when they saw themselves as the hero, Monáe has lived up to the potential of Afro-futurism’s expansiveness by reconceptualizing the Black queer experience in an alternative reality.

Photographed by Shaniqwa Jarvis.

Marc Jacobs blazer, top, trousers, belt, and turban; Liudmila Footwear Drury Lane 100 Boots, €950, available at Liudmila Footwear; 3.1 Phillip Lim earring.

Together, the Dirty Computer flashbacks paint a picture of Jane’s free-spirited lifestyle despite constant surveillance and the threat of persecution. This includes peacefully entertaining two lovers simultaneously. One of them is Che, played by Jayson Aaron. The other is Zen, played by Tessa Thompson, the woman long-rumored to be Monáe’s off-screen lover. Thompson appears prominently in two of the music videos that were released ahead of the album — “Pynk” and “Make Me Feel.” Both videos were packed with intimate sexual undertones that teased fans thirsty for tea about Monáe’s actual dating life. Like Beyonce’s Lemonade — which set a standard of excellence at the intersection of Black womanhood, music, and film — Monáe’s project is one in which a private artist tantalizes fans by toeing the line between the personal and political.

“The most important thing is that I'm honest about who I am and the journey that I have been on,” Monáe says. “The people that I respect and admire from my parents, to some of my biggest heroes, were not perfect. They made mistakes. They always encouraged me to be better than them. My job is to encourage anybody who is looking at me as an example to be better than me.”

She says this confidently, and yet at an advanced screening of Dirty Computer at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center, she admits that she is nervous. She emerges on the stage in her signature black and white and thanks the audience for coming. This is the realization of a dream, she divulges with her hand clasped in front of her, obviously moved by the many bodies in chairs.

It’s been four years since she’s released an album — she’s been busy out there mainstreaming as an actress in Oscar nominated films like Hidden Figures and Moonlight. This is her first time coming back to her fringey musical roots and the gaggle of press, artists, and fans are excited to see how her newfound stardom and eccentric spirit can merge. The room is full of people who appear to be marching to the beat of their own drums. To my left is my hairstylist friend Kyrsten Oriol, who also worked on several of Monáe’s recent music videos. To her left is the famed queer visual artist, Mickalene Thomas, dressed in all black. To my right is a white supporter, who will later passionately thank me for my animated reaction throughout the film. Somewhere behind me is Orange is the New Black’s Adrienne C. Moore, and a girl who curates one of my favorite fat-themed Instagram accounts. Common and Lupita Nyong’o casually converse two rows ahead of me. None of them are disappointed at the end of the night.

In the weeks that follow, Monáe will come out publicly and officially as queer, and that moment will be heralded as a “coming out” for Monáe. But just because Monáe has made a public statement, doesn’t mean she’s crossed some threshold from a dark closet into the light. “I've been living my life in the way that I have for a long time,” she explained to me. “I don't get caught up in how writers or people discuss what it is. The truth of the matter is: I move when I'm ready to move. The truth is that this was a time for me to discuss my sexual identity. I said it before and I'll say it again: I'm proud to be a young, Black, queer, American woman.”

However, the path to Monáe’s announcement of pride wasn’t without obstacles. Like me, Monáe grew up a member of a big working class family in the Midwest — me in Chicago and her in Kansas City, Kansas. At last count, Monáe has around 50 first cousins. Both of our families wear their religious beliefs like badges of honor. And neither of us have been immune to the politics of respectability that often flow through the fabric of families like ours, intending to keep us safe, but sometimes stifling us in the process.

“It hasn't been a perfect response across the board,” she tells me about her family’s reaction to her declaration about her sexuality, and I would have been genuinely shocked to find out otherwise. Monáe says that her parents, who have always been in their daughter’s corner, have received concerned phone calls from some extended family members.

“Some people would say certain things that were not supportive. They just don't understand. It's like, ‘this is how it’s supposed to be,’ ‘why is she doing this?’” she says.

In a way, this juncture of Monáe’s career symbolizes the interplay between her “machines” and her humanity. At the same time that she is reaching the upper echelons of her career, she is using Dirty Computer to dig her heels even deeper into those Kansas City roots, with several references to her upbringing and hometown. While she clings to where she’s come from, she’s become willing to go public with a queer identity that may create an even deeper wedge between them. “I am grown. I'm not the little girl living in Kansas who never asks any questions or felt afraid to follow my heart,” she says. But as Monáe brings forth who she is, with human qualities like nervousness, honesty, vulnerability, her strongest musical and visual work to date still offer her up as a hard drive needing to be cleaned.

“I have little cousins who are still there,” she admitted. “And they are ostracized and pushed out of their homes. People are telling them that they're sinning or they may be going to hell. For me, it's important to let them know I'm their cousin, I understand what you're going through. You're not a freak, you're not a deviant, you're not a sinner. There is nothing wrong with you.”

***

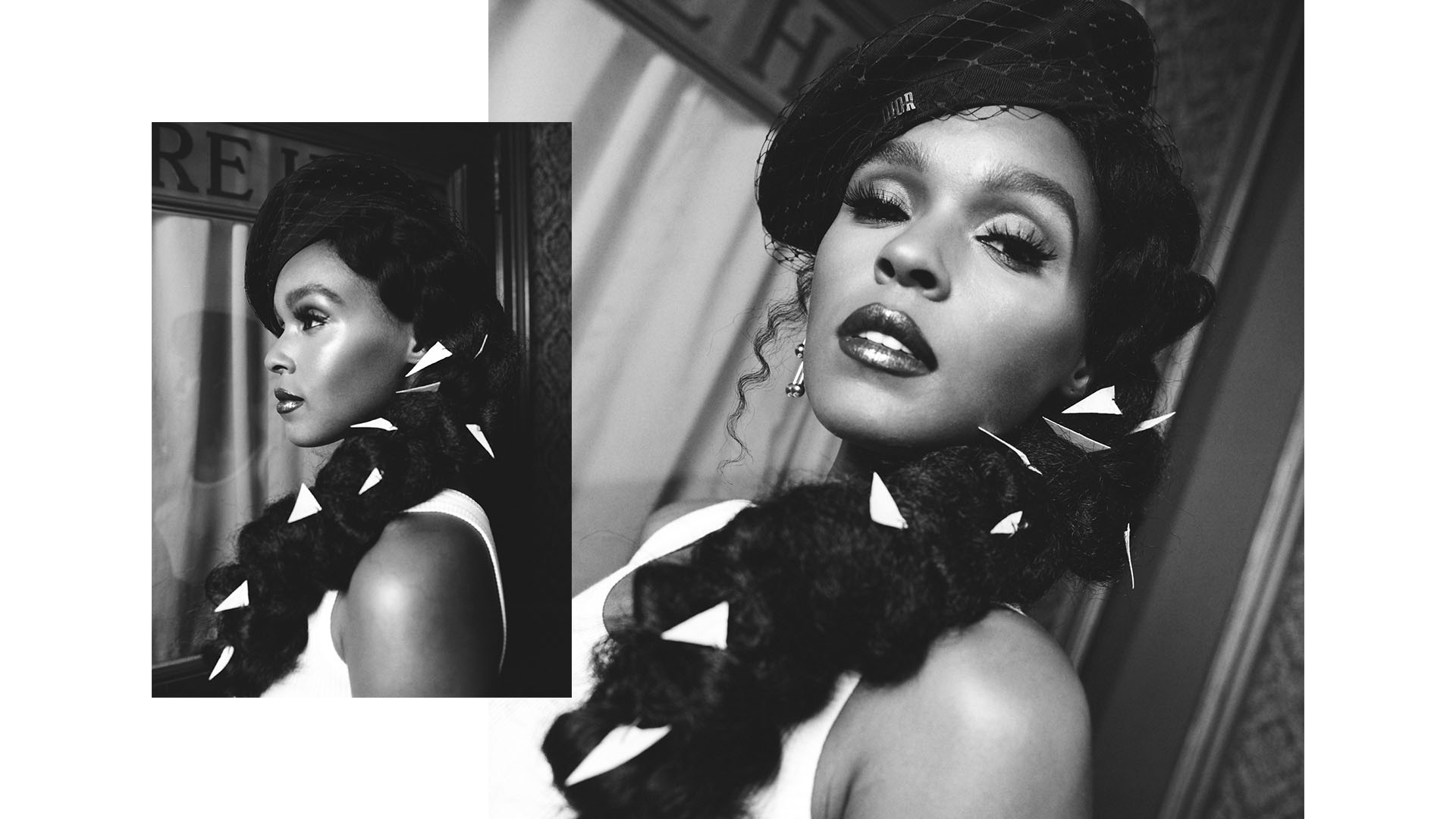

Running parallel to her next-level creativity, is a work ethic I witnessed firsthand during my first face-to-face interaction with Monáe, weeks before the Dirty Computer screening. On the morning of her photoshoot at the United Palace Theater in Harlem, I was blessed with a barely audible “hey” as she strode past me, towards the auditorium where Shaniqwa Jarvis would photograph her. She was in work mode and laser focused. Monáe requested a closed set and asked that the soundtrack to Alfred Hitchock’s Vertigo play from the speaker as mood music for her shoot. (Not even her productivity is immune to her mysterious whims.) When I asked her about this professional trance, she broke it down this way:

Running parallel to her next-level creativity, is a work ethic I witnessed firsthand during my first face-to-face interaction with Monáe, weeks before the Dirty Computer screening. On the morning of her photoshoot at the United Palace Theater in Harlem, I was blessed with a barely audible “hey” as she strode past me, towards the auditorium where Shaniqwa Jarvis would photograph her. She was in work mode and laser focused. Monáe requested a closed set and asked that the soundtrack to Alfred Hitchock’s Vertigo play from the speaker as mood music for her shoot. (Not even her productivity is immune to her mysterious whims.) When I asked her about this professional trance, she broke it down this way:

“For me I have to focus when I'm at photoshoots. It's different from when I'm in my studio and I'm paying for my own studio time and I'm around all creatives and that's all we're doing. This is a business. It's not just music. I'm in the music industry,” she says with emphasis. “And as a businesswoman I always want to make sure I'm on time, I always want to make sure I'm making time. I always want to make sure I get to my next appointment on time. You know, being a time traveler comes with great consequence.”

This is a virtue that started when she was a teen working a retail job — something else we have in common — to help pull weight in her working class family. After she was discovered by Outkast’s Big Boi, she landed a record deal and later, her own imprint where she has signed and collaborated with acts like St. Beauty and Jidenna. She was lucky enough to call the late legend Prince a mentor and a fan. But for the first few years of her life in the spotlight, she still committed herself to wearing only black and white tuxedos to pay homage to those working class origins, mimicking the daily uniforms that blue collar workers are often subjected to. In the Dirty Computer single “Django Jane,” she rhymes, “Momma was a G, she was cleanin' hotels / Poppa was a driver, I was workin' retail / Kept us in the back of the store / We ain't hidden no more” just before a line about her Oscar and Grammys nods.

Monáe is the quintessential girl who can do both. She can brag through humility. She can jubilate in the face of oppression. And she can seduce in a pair of see-through mesh jeans with nothing but a flesh colored thong underneath, or in a pink pantsuit. “I'm a very complicated woman,” she told me when I asked her about her position in a new class of Black sex symbols that are queer, androgynous or just plain nerdy. “I think everybody has those moments where you want to turn it off. You don't want to be admired. You don't want to be objectified. I look at myself as a subject, not an object. A subject to study, to the end of time.”

Miu Miu Logo Plaque Ribbed Vest Top, $230, available at Farfetch; Christian Dior beret; Tiffany & Co. earring.

***

In June, Monáe will embark on the nationwide Dirty Computer tour. If you’ve ever seen her perform live, then you know that her calm demeanor is replaced with a fiery display of raw talent when she hits the stage. She sings and dances with her whole body, moving around the stage to the beat of a live band. I want to know how she does it, and I ask her if she has a pre-tour ritual. But I hit a wall. “I do. But I prefer not to give it away,” is all she offers.

In June, Monáe will embark on the nationwide Dirty Computer tour. If you’ve ever seen her perform live, then you know that her calm demeanor is replaced with a fiery display of raw talent when she hits the stage. She sings and dances with her whole body, moving around the stage to the beat of a live band. I want to know how she does it, and I ask her if she has a pre-tour ritual. But I hit a wall. “I do. But I prefer not to give it away,” is all she offers.

Instead she paints a wonderful picture of the experience she hopes to have with fans. “When I would watch people like Michael Jackson or Prince or Lauryn Hill, they made me feel like I was being transported to another place. It was something special and it made me want to give that experience to anybody who comes to the show. So that's what I aim to do, and I aim to do it like it's my last time.”

At the end of our chat, just when I think she is grateful to be done with me and have a few moments to herself, she surprises me with a question of her own. “Where are you from? You sound like you're from the Midwest.” She revels in the familiarity of my accent and promises to read my work. In that moment, she has unknowingly delivered on one of her promises. I — a young, Black, queer, American woman from Chicago — feel seen in the way that only another woman who has lived in the similar margins of society can.

Special thanks to United Palace.